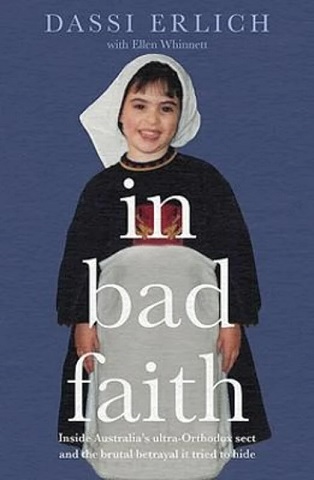

Whatever you are doing now, please stop, jump online, and order a copy of the book “in bad faith” by Dassi Ehrlich which was released for sale last week.

Prepare to read the story of how she was abused, and contemplate the public contour that she had to navigate to obtain justice. Be confronted. Realise that the crime of sexual abuse is humanity at its worst.

Most of the books I read are for enjoyment, but also to broaden my knowledge and perspective on many important social and cultural issues. Not on this occasion. Before I started reading “in bad faith” I knew it was something I had to do in order to fully comprehend the magnitude of experience of an innocent child falling victim to circumstances that were no fault of her own. I was expecting to be disturbed by the feelings of a young person who suffered sexual abuse and who was simultaneously trapped by an inability to know how and where to turn for support. And I was disturbed. Even further by the compounded and inexcusable coverup in support of the perpetrator orchestrated by senior Jewish community leaders who bring shame and disgrace, a shanda on the community in the name of the Jewish religion.

My exposure to the story of Dassi Ehrlich’s plight, and that of her sisters, was initially through media publicity. I came to know more about the story through the live streaming of farcical court appearances in Israel (74 court hearings all up) which appeared in my feed from my friend Adam Segal whose relentless support for justice was fearless. Many other former Australian journalists, educators and community identities who I have personal connections with were involved in this matter, much of which I only learnt from the book.

What strikes me most about Dassi’s story is the depth to which both the emotional and physical abuse shaped her adolescence and how her entrapment within the insular and male controlled Adass community left her with nowhere to turn. Unable to confide in her peers and family, and with no line of social support, she was driven to near suicide. Being thrust into the medical system of a world she had no exposure to became the cause of more unfathomable trauma. At the same time, it opened up a new world for her to experience. Within that world she received the support, education, and social connections that were denied to her youth. With it, her humanity rose above her subjugation.

When I was in my teens I visited Melbourne on many occasions. It was around time that Dassi and others were being sexually molested by Malka Leifer. I walked the streets that she describes in her story. At the time I had never come across ultra-orthodox Jews before, and was initially enamoured by their appearance and seeming piety. Many of my Modern Orthodox friends spoke of their community very disparagingly, some with outright hostility. There was a lot I didn’t understand, but as I grew in my Jewish identity I came to realise that the charedi values and expressions (hashgafa) of these people were so very different to my own. I have no doubt that many charedi Jews have values (middot), knowledge and faith (emunah) that is as inspiring as it is pious, and their righteousness should not be judged by a few criminals amongst them. However, more than ever I am committed to the Judaism of religious Zionism, a Jewish approach that engages and infuses all aspects of living. That includes secular engagement, secular education, and exposure to alternative cultural norms.

Had the insularity of Adass not been a barrier, the abuse may still have occurred, but the pathway to support and escape for Dassi may have been easier to identify and access.

The Jewish community across its diverse spectrum of religiosity is far from immune to the crime of sexual abuse. As a youth counsellor I had to deal with abused Jewish children who have been left with lifelong scars by a paedophile who now roams free. The experience of sourcing professional support for them matured me. I was not surprised to see the victims completely disassociate from Jewish community affiliation. The community had failed them and did not deserve a second chance.

The word heroine should not be used lightly, but Dassi Erlich is a heroine. She had to rise above the crimes of her parents and Malka Leifer, and sacrifice her privacy in order to submit herself to a public campaign for justice. She was ultimately successful with both.

The most impressive element of Dassi Erlich’s experience is how the advocacy to extradite and charge Malka Leifer reached the highest levels of Government both in Australia and Israel. With bipartisan support and a parliamentary motion, the case was taken by the Prime Minister of Australia to his Israeli counterpart. The alleged (and since proven) interference and corruption from the Israeli Minister of Health (Yaacov Litzman) acting to protect and defend Leifer was significant enough to potentially bring down the Government of Israel. Politics in Israel is, with good reason, not respected and the entire nation seems to work in spite of, not because of its political processes. As Dassi noted, the prime concern of Bibi Netanyahu was self-preservation. Both the judicial system and the political system in Israel became intolerable for Dassi and her sisters, and by extension to the people of Australia.

Dassi’s story inspires because she recovered from her trauma, chose life over despair, and saw her abuser convicted. Sadly, many victims of sexual abuse are unable to pursue justice through the police and courts. Many are unable to recover, let alone reveal the abuse they suffered. Some are unable to remove themselves from self-harm, and some do not live to tell their story. Not all victims are survivors.

It is important that this story has been told. This book has been well written, to capture enough of the abusive conduct and its emotional trauma without going too far with descriptive detail (in sensitivity to the victim, not the reader). It is a reminder that anybody who aids and abets an abuser, or even turns away from abuse in silence is culpable. It reveals a truth, that religious appearances account for nothing but personal conduct accounts for everything.

If Dassi Ehrlich continues her journey, the next time innocent Jewish children are groomed by perverts then maybe the right channels of reporting, intervention and support can be readily identified by those who hold a duty of care. Many lives will be saved.